Celebrating Disability Pride Month 2025 Stories

To celebrate Disability Pride Month 2025, Cold Tea Collective is spotlighting ten powerful leaders across the Pan-Asian diaspora who are boldly redefining visibility, pride, and advocacy at the intersections of disability, culture, and community.

Whether late-diagnosed, born disabled, acquired, or navigating complex relationships to disability and culture, each of these individuals offers a powerful reminder: We don’t have to be “fixed” to belong.

Across their journeys, several key themes emerged:

Cultural silence, stigma & shame

Many grew up in households or communities where disability was taboo or viewed with pity. Cultural values around perfection, emotional restraint, and family honor often led to silence and suppression, especially when it came to neurodivergence or mental health.

Intersectionality & identity conflict

Being both Asian and disabled often led to feelings of disconnection or invisibility. Navigating these intersecting identities, sometimes across borders, adoptions, or generational gaps created a complex emotional landscape. But over time, many found strength in honoring all parts of who they are.

Barriers to diagnosis & support

Systemic racism, research bias, and cultural misunderstandings often meant that many were misdiagnosed, undiagnosed, or ignored by healthcare and education systems. For some, it took years, even decades, to receive recognition or accommodations.

Redefining pride & unmasking

Disability pride was not something inherited; it was reclaimed. Through unmasking, community, and self-advocacy, each changemaker learned to live more authentically. Their journeys reflect a powerful reframing of disability: not as something to fix, but something to honor.

The power of representation & community

Visibility is more than optics; it’s survival. Representation across leadership, media, and daily life helped affirm identities that had long been erased. Finding or becoming the representation they never saw helped each person feel less alone and more connected.

Disability as a catalyst for innovation & leadership

Many found that disability drove creativity, empathy, and transformation. Whether through art, policy, storytelling, or research, these changemakers are reimagining what inclusive systems can look like and challenging assumptions of who gets to lead.

Urgency, systems change & the path forward

While there has been progress, the work is far from done. From policy to education, media to healthcare, each changemaker called for deeper representation, structural access, and meaningful investment in disabled voices, especially from multiply marginalized communities.

Read on to meet the changemakers, and learn how each is reshaping what it means to be disabled and Asian through their advocacy, leadership, and lived experience.

10 people redefining what it means to be disabled and Asian

Vanni Le (she/her)

A neurodivergent Vietnamese American DEIA advocate and the Senior Manager of Entertainment Partnerships at Disability Belongs™. She has advised major studios, production companies, and independent filmmakers on over 100 films and TV episodes to promote authentic portrayals of disability and inclusive hiring practices behind the camera. Most recently, she served on the Cultural Story Trust for Disney Animation’s “Wish”, which featured the studio’s first physically disabled Asian character.

“Everyone has multiple identities and facets to themselves.”

Growing up as a Vietnamese-American kid in Florida, Le rarely saw herself represented in her daily life or on screen.

“When you don’t have that kind of diversity in role models, society often reverts to stereotypes.” Struggles with math and behavior in school signs of undiagnosed ADHD and dyscalculia were overlooked due to the model minority myth.

Advocacy journey

“I was first drawn to disability advocacy because of the opportunity to effect intersectional social change.”

Though 1 in 4 adults in the U.S. are disabled, Le notes many more may go undiagnosed or remain undisclosed due to systemic barriers, especially within communities of color. In her work, she has faced both racial microaggressions within disability spaces and ableist microaggressions in AAPI communities.

It’s important to have these conversations intersectionally, as these communities are not mutually exclusive. I want to encourage people to think more deeply about their inclusion practices and think about who they may be unintentionally leaving out.”

Disability pride

“Now that I’m older, I’m really proud of the person I’ve become with all of my intersectionalities. As Sandra Oh says, ‘It’s an honor just to be Asian.’”

Disability is part of identity, not something to be ashamed of. Le’s work in media and cultural change helps shift the narrative away from marginalization toward authenticity and empowerment.

She encourages people to seek community in both their personal and professional lives, places “who will truly allow you to be your most authentic self.”

Khris Baizen (he/him)

A neurodivergent, hearing-impaired Chinese-Filipino mixed Asian American creative, husband, and global business events leader based in Los Angeles. Raised in a faith-based missionary family where “silence was strength and masking was survival,” Baizen grew up labeled as “too much” and “never enough” too emotional, too intense, too sensitive. These very traits, once seen as flaws, became the core of his leadership. Today, he leads with empathy and clarity, creating brave spaces where others can show up with their full story intact.

In a first-generation household where mental health was never discussed, Baizen learned early to internalize pain and suppress his differences. “I carry the reverence and resilience of my culture while also dismantling the shame that came with being ‘different.’”

Advocacy journey

As Baizen began speaking openly, others resonated and leaned in. “I became an advocate the day I realized that my lived experience—my anxiety, overstimulation, hyperfixation, sensitivity was not just mine.”

“This wasn’t just healing work. It was a new form of leadership. The more I showed up fully, the more others did too. Advocacy became the byproduct of honest living.”

Disability pride

“Disability pride isn’t just personal, it’s ancestral work.” Baizen reflects on the cultural silence around pride and how it often looked like

“self-erasure in service of the collective.”

Baizen urges others not to overperform for acceptance. “The very things that make you feel out of place now might be the reason someone feels safe with you later. You are strong because you see the world differently. And that perspective is priceless. Build your community, speak your truth (even if it shakes), and know that you don’t need to be like them to lead them.”

Saran Tugsjargal (she/her)

A global leader and 2024 D-30 Disability Honoree. She serves on state and national boards and made history as the first youth commissioner on the California Department of Education’s Advisory Commission on Special Education (ACSE). Tugsjargal identifies with multiple disabilities, including Autism Spectrum Disorder, and advocates across education, policy, and social welfare to ensure systems are designed by and for the people they serve.

“Being disabled and Mongolian didn’t come with visibility; it came with being invisible.”

Tugsjargal’s identity is deeply rooted in her Mongolian heritage – a culture rich in history, nature, and deep community. But growing up, disability was met with shame, and her ethnicity was often erased or misunderstood.

Still, she learned that “being disabled and Mongolian aren’t contradictions. They are my truth, where I hold pride and strength, purpose.” She doesn’t choose between her identities; she honors all of them.

Advocacy journey

Tugsjargal struggled to fit in throughout her childhood, as she was pulled out of class for services, mocked by peers, and left behind by systems that didn’t understand her. “It wasn’t just about a lack of support. It was about a system that wasn’t built for students like us.”

Her shift into advocacy began when she became a caregiver at 15 for her twin cousins, both English Learners. While navigating school systems on their behalf, she realized the deeper issue:

At 16, she became the first Mongolian American official in California and she hasn’t stopped since. “I kept using my voice to fight for students and families, shaping federal policy, and now bringing that advocacy back to Mongolia.”

Disability pride

In Mongolian culture, disability is still taboo. Tugsjargal is working to change that. “Disability pride, to me, means owning our stories loudly, unapologetically, and in community.”

Tugsjargal encourages others to express themselves however they need through art, music, advocacy, gaming, or writing. “I speak up. I mentor other Mongolian youth with disabilities. I create space to share our experiences and uplift our accomplishments.”

“You and your disability are not a burden. You are a force. And remember: you can love your culture deeply while still challenging the parts that silence you. That’s not disrespect. That is what change looks like.”

See also: Breaking free from the model minority myth as a neurodivergent Vietnamese American

Marisa Hamamoto (she/her)

An internationally recognized disability inclusion champion and the first professional dancer named a People Magazine “Woman Changing the World.” A proud fourth-generation Japanese American and spinal stroke survivor, she is also a late-diagnosed autistic living with PTSD.

As the founder of Infinite Flow Dance, an award-winning nonprofit dance company that employs dancers of all abilities, Hamamoto has spent the past decade building a culture of belonging through art and advocacy. Her work has been featured on Good Morning America, NBC Today, and Forbes, and she has spoken at the United Nations and Apple HQ. She was also a finalist for Best Film in the 2025 Easterseals Disability Film Challenge for Killed It.

“I grew up not knowing that I had a disability. My autism diagnosis definitely revealed a lot […] clarified a lot of the challenges I grew up with.”

Hamamoto’s spinal stroke happened at age 24 while in college in Japan. Her autism diagnosis came at age 40, and PTSD at 38.She shares that she struggled socially, misunderstood jokes and figurative language, and was labeled as “socially stupid.” Her parents didn’t recognize this as neurodivergence. “

The family hid disability out of shame: “It’s embarrassing to have a child with a disability […] just hush-hush.”

Advocacy journey

After her stroke, Hamamoto founded Infinite Flow Dance in 2015. “I didn’t have a choice but to become a disability advocate […] I had to learn early on about access accommodations… I had a very strong sense of what discrimination was.”

Her leadership led her to advocacy, and her work redefines disability as a source of innovation: “There’s just so much creativity that’s born when you center disability.”

Disability pride

“I don’t know if I consider myself a disabled and proud person… It’s just one aspect of who I am and what makes me unique.” Hamamoto embraces her autism as a strength: “I’m able to focus on one thing for a long time […] I can go deeper than anyone else.”

She coined what she calls the “creative model of disability”: “Disability is probably one of the strongest catalysts for innovation […], so much has been created as a result of designing for disability typewriters, email, sliding doors.”

Hamamoto encourages others to connect online: “You’re not alone. There are many of us. Do a quick Instagram search and you’ll start to find us. When you start to see that there are disabled Asians out there doing incredible things, you realize: okay, that’s who I am.”

See also: Naomi Osaka’s precedent for mental health in sports for Asian diaspora

Tiffany Yu (she/her)

A car accident survivor, a first-generation daughter of a Taiwanese immigrant and a Vietnamese refugee, and the founder and CEO of Diversability, a global movement to celebrate disability pride and community. She became disabled at age 9 and was later diagnosed with PTSD from the trauma and cultural shame she was taught to hide. Today, she’s also the creator of the Disability Empowerment Endowed Fund and author of The Anti-Ableist Manifesto.

“Disability could be this health diagnosis [ …], but it’s also this beautiful community, culture, history, pride, empowerment, the same way I see my Taiwanese American identity.”

Tiffany reflects on how growing up in a household where disability meant shame shaped her silence: “I buried my feelings behind a smile […] I now call this internalized toxic positivity.”

Advocacy journey

Yu never set out to be an advocate. But her own experiences of silence, stigma, and isolation eventually inspired her to create Diversability.

“Sharing my story allowed me to uncover other parts of it, especially around the dynamics of how my Asian culture played a significant role in how I saw myself as an Asian American woman with a disability.”

Her advocacy is driven by a commitment to intersectionality:“Disability justice is inherently intersectional. It connects with racial justice, gender equity, LGBTQIA+ rights, and economic justice because disabled people exist in every community.”

Disability pride

Yu recalls the moment she began reclaiming her story. In 2019, she decorated her wrist splint with an illustration of her nine-year-old self hugging the “elephant in the room,” with the word proud written across the strap.

“This splint felt a little bit like my middle finger to the world… It felt like the best kind of self-love to give my hand its time in the spotlight. Our disabled bodies are beautiful.”

Reflecting on her journey, Yu shares that despite how her mother doesn’t understand her work, she is proud of herself. “My journey makes me proud. My disability makes me proud. Who I have become makes me proud.”

The advice Tiffany Yu gives to others is to find community. “You are not alone, even if it sometimes feels that way. Your disability is not something to fix or erase. It is a valid and powerful part of who you are. It’s okay if it takes time to unlearn the messages you were taught. Find community, whether online or in person, where your experience is affirmed. And give yourself permission to define your identity on your own terms.”

Jennifer Miyaki (she/her)

A neurodivergent, mad, disabled Asian American woman from an immigrant and mixed-status family. She is a late-identified autistic, ADHDer, and OCD-diagnosed student who also identifies as hard-of-hearing and uses a walking cane for a neurological condition related to balance and coordination. A recent UCLA’s Master student, she was most recently a student coordinator with UCLA’s Disabled Student Union (DSU) and Bruin Neurodiversity Collective (BNC), where she advocated for intersectional access, community, and policy change across the University of California system.

Miyaki is half-Chinese and half-Japanese, with strong ties to her Burmese heritage. Her family history includes generational trauma from WWII internment to colonial violence experiences that were never spoken aloud. “Trying to explain my ethnic background has always been like trying to explain a patchwork quilt.”

“Disability, especially neurodivergence and mental health disability, were not talked about, not understood, and attempts to initiate conversations were not typically welcomed.”

Her diagnoses came after more than 20 years of being overlooked by family, systems, and medical professionals. “The challenges I faced weren’t personal flaws, they were reflections of a society that wasn’t built for me.”

“It took them overlooking my speech delay, bullying, panic attacks, long morning routines, treatment-resistant depression, and multiple hospitalizations to finally suggest that I might be neurodivergent.”

Advocacy journey

Miyaki found her voice through UCLA’s Disabled Student Union (DSU) and Bruin Neurodiversity Collective (BNC).

“Before, disability was never discussed in my family […] Finding community helped me realize I didn’t have to frame my disability as a superpower to accept myself.”

Disability pride

“Disability pride has become the wind in a flag I’ve always had. And I don’t wave it alone.”

Miyaki celebrates disability pride through speaking, creative expression, and shared experiences with peers. She was one of the graduating student commencement speakers at UCLA’s Disabled Student Graduation and painted the disability pride flag on her stole.

“Celebrating shared journeys and meaningful connection gives me the strength to wave my flag more furiously.”

Miyaki emphasizes that navigating disability in Asian communities doesn’t have to follow one path. “Reframing your disability doesn’t have to start or involve your family it can start with yourself. Even if your family continues to overlook the rainbow for random indiscriminate colors, you can still foster your internal disability pride flag.”

See also: Celebrating neurodiversity in Asian American communities

Jenny Mai Phan, Ph.D. (she/her)

A Vietnamese, second-generation American and the first in her lineage to earn a Ph.D. in education. She is a Research Assistant Professor in Bioengineering at George Mason University, where her work focuses on community-engaged research around accessibility and well-being. She discovered her own neurodivergence late in life through her children’s diagnosis process. As a proud autistic mother and academic scholar, she bridges lived experience and research to serve disabled communities locally and globally.

“To me, being disabled and Asian means a blend of unique cultural, linguistic, and neurodivergent spices mixed together to make a captivating story, and in my culture, we use star anise and Saigon cinnamon sticks to flavor our noodle soup called phở.”

Phan compares her identity to the flavors in phở, noting how her Vietnamese heritage and neurodivergence combine into something rich, layered, and often misunderstood. She shares how stigma, internalized ableism, and “invisiblization” shaped her early experiences.

Food has been a complex but meaningful point of connection in her family, one filled with autistic and neurodivergent members.

Advocacy journey

Phan’s advocacy journey began with her family and deepened through conversations with other Asians who had been missed or misdiagnosed. She recalls how mental illness and neurodivergence were not openly discussed growing up, even though they were clearly present.

“I started out as a parent advocate for my children before I discovered my own neurodivergence.”

“I gathered from their stories about how misunderstood they feel by professionals and society. I resonated with their stories. Those stories influence my advocacy at the local, national, and world level.”

She now uses her voice and research to bridge mental health disabilities with conversations on autism and neurodiversity.

Disability pride

Phan breaks the cycle of silence and shame she was raised with by openly discussing disability with her family. Her kids are proud to be Vietnamese American and neurodivergent, and they’re learning self-advocacy early. “My spouse, kids, and I talk very openly about disability as if it is a typical part of our lives and the lives around us. There is no shame. Only embrace […] All of this said, this does not mean there are no struggles and challenges. We have plenty of those. We embrace them, too.”

Phan urges others to connect, share stories, and build local support. Whether through online dialogue or community potlucks, she believes in starting small and building together.

“My advice is to reach out to one of us who is putting our stories out in public. If we cannot offer much, we can at least offer our experience and that might help you feel less alone […] You can start a club to meet regularly to have this local support. Bring food and fellowship.”

See also: Honoring the past, celebrating resilience: Fifty years after the Fall of Saigon

Hari Srinivasan (he/him)

A Ph.D. student in neuroscience at Vanderbilt University, where his research focuses on sensorimotor systems in autism. He is autistic, has ADHD, and experiences a range of motor, sensory, and communication differences. Hari has limited spoken language, though that continues to improve, proving that you’re never too old to learn and grow. A graduate of UC Berkeley with a psychology degree and a minor in disability studies, he serves on several disability nonprofit boards and advisory groups and is a published writer and TEDx speaker.

“I grew up in Silicon Valley… where I saw two extremes: immense pressure on typical kids to excel, and in sharp contrast, zero expectations for someone like me, the disabled Indian kid who needed to be tucked away in a special ed classroom, out of sight and out of mind.”

Srinivasan experienced what it meant to be both hyper-visible and invisible. His peers were encouraged to reach for the stars, while he was seen as a disruption to the “American Dream.” Within the broader Asian community, disability was shrouded in silence.

Yet, Srinivasan found cultural resilience in his Indian heritage. “The Asian emphasis on family and interdependence taught me that needing support isn’t shameful.” He draws strength from Indian philosophical traditions that value introspection and complexity, helping him anchor his sense of worth beyond productivity.

Advocacy journey

“My journey began because I didn’t see people like me […] not in research, not in policy, not in higher education, not even in advocacy spaces.”Inspired by the late Judy Heumann, Srinivasan became a leader for minimally and non-speaking autistic individuals. He’s proud to see more entering higher education.

“The Bhagavad Gita reminds us that change is the only constant, and that inaction is not an option.”

His advocacy is driven by small actions that ripple into systemic change. He shares his story through writing, speaking, and building new roles like the one created for him at the Berkeley Disability Lab, and he attributes Professor Karen Nakamura for creating meaningful work that plays to his individual strengths.

Disability pride

Srinivasan believes in full inclusion, not partial accommodation. While Western norms prioritize independence, he embraces the interdependence already valued in Asian culture. His work challenges the narrative that disabled people must conform to narrow molds of ability. “It’s about claiming space that recognizes autism is both an ability and a disability […] not either-or,” he shares.

“You don’t have to choose between your culture and your disability identity—they can co-exist. Don’t wait for permission to take up space. Your existence already justifies your belonging.”

Maddy Ullman (she/her)

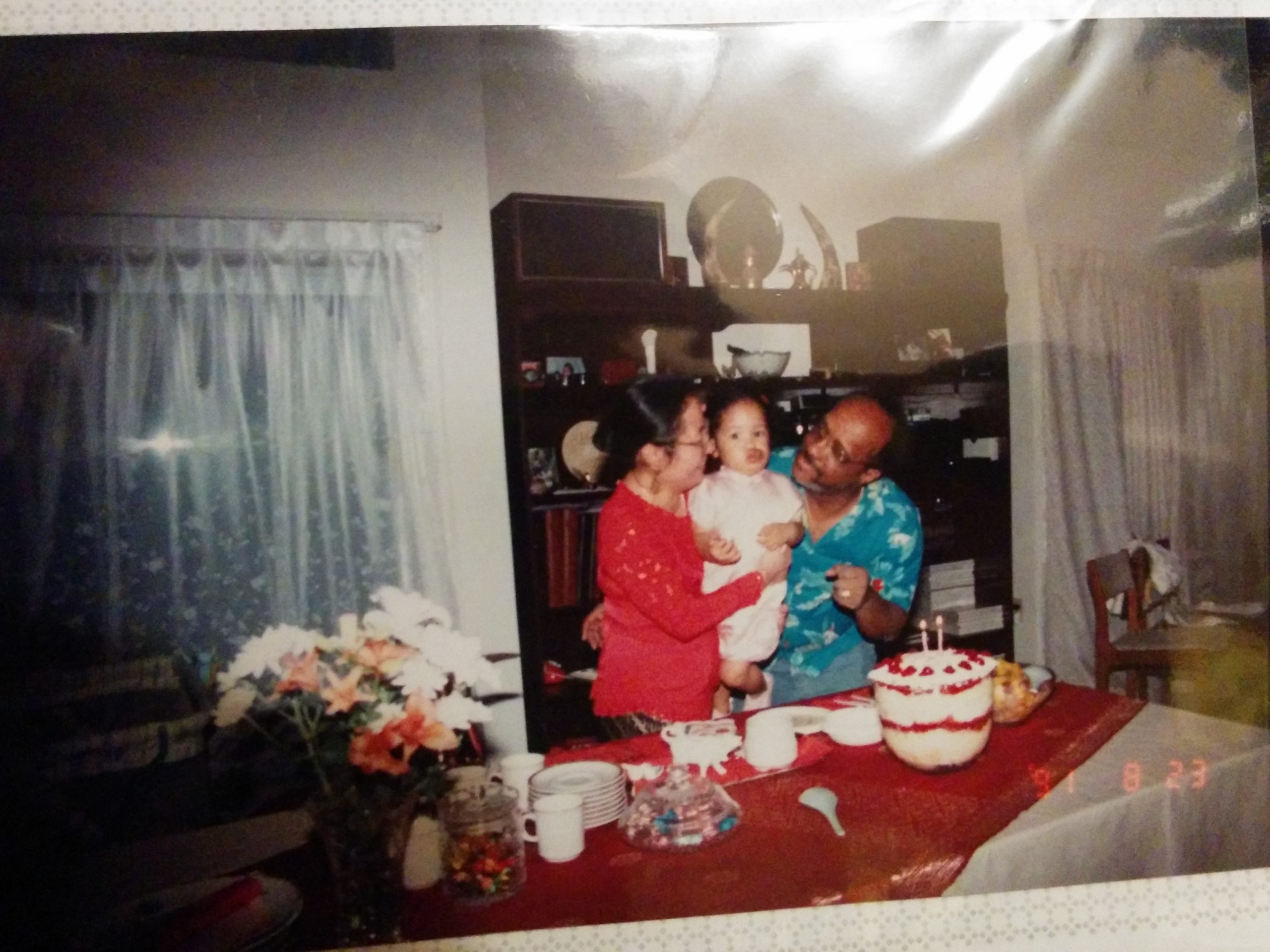

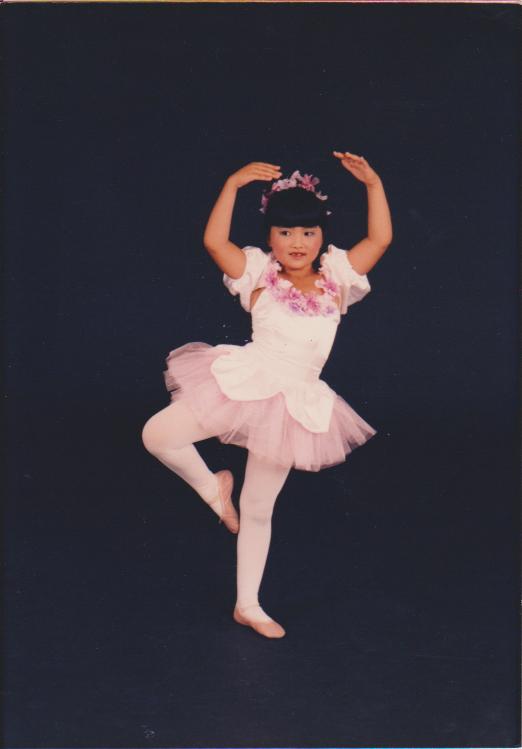

A Hong Kong adoptee and disability-in-film consultant, storyteller, and advocate based in Dallas, Texas. She lives with cerebral palsy, diabetes, ADHD, and more. Passionate about authentic disability representation, Ullman has consulted for major studios including Netflix, Warner Brothers, and Disney, most recently contributing to “Wish”, the first Disney film to feature a visibly disabled Asian-American character.

“What a cocktail of life I have as an Asian adoptee woman with cerebral palsy, diabetes, ADHD, and so much more! These intersecting identities have shaped my life in ways that only the universe, God, or whatever else one believes in could orchestrate.”

Ullman shares that she cannot talk about disability without talking about adoption and vice versa. “Sometimes, simply existing feels like trying to stuff the whole ocean into a lake and always overflowing. Fighting so hard to be alive. To be seen. To be heard. To not be a burden in an ableist society. Sometimes it brings me to my knees (metaphorically, of course). And then realizing I can thrive.”

Advocacy journey

“I realized I wanted to be who little Maddy needed to see growing up. If I had seen disabled Asian representation, it would have changed my life.”

Ullman says she always just wanted to be “Maddy” to blend in. But growing up in a town that was 0.8% Asian, that wasn’t possible. After contributing to “Wish”, her path became clear.

Receiving her first wheelchair this year further energized her advocacy. “Becoming an ambulatory wheelchair user opens my eyes to the lack of accessibility, and every day is an adventure. My wheelchair has allowed me to do more with less pain, and I love it. In 20 years, I will still be able to walk because of it.”

Disability pride

Ullman says that being disabled has shaped her into who she is. “If someone came up to me and said, ‘I could take away all of your disabilities right now, and you never have to deal with them ever again,’ I would say ‘No.’”

“I love who I am with disability. It is complex, heartbreaking, and devastating at times, but it has truly built me, brick by brick, into the person I am today. And with that, I can make change,” she says.

Ullman encourages others to “exist and treat yourself with grace, wherever your body is that day. Feel the feelings, and be your best hype person.”

“Work with your disability, not against it. You don’t have to be inspirational. You don’t have to overcome.”

Most importantly: “Find your community. You are not alone. Find other Asian people who are disabled, because the community is the most powerful thing.”

See also: Joy Ride arrives at an intersection of inclusive storytelling for the Asian American diaspora

Olivia Hall (they/she)

A late-diagnosed AuDHD (autistic and ADHD) transracial Chinese adoptee who grew up in suburban Ohio. They are a community engagement specialist, advocate, and creative who empowers BIPOC, AANHPI, disabled, and neurodivergent communities through storytelling and outdoor initiatives. Their work is rooted in community care and solidarity, and outside of that, Hall enjoys crafting, spending time in nature, and watching films.

“Being disabled and Asian to me is completely grounded in intersectionality.” As someone who is both late diagnosed and raised outside of their ethnic heritage, Olivia says their upbringing often made them feel out of place even within their own self-understanding. “Both my lack of understanding and lack of community with regards to both of these facets of my identity growing up contributed to feelings of isolation and disconnection.”

But in the past few years, Hall has begun connecting with both their cultural and disability identities, which has been “exceedingly beneficial in terms of enabling me to form community and interface with the world better.”

Advocacy journey

“My becoming a disability advocate is partly rooted in a general interest in / caring about other people.”

Their advocacy was also catalyzed by their own discovery of being neurodivergent.“After growing to understand that about myself, I continued to not only learn more about my specific disabilities, but also other disabilities more broadly, and get involved in the disability space.”

Disability pride

“Though I’m sure it’s imperfect, I try to embrace being disabled in my life by trying to be myself.”

Since discovering their neurodivergence, Hall has become better at advocating for their needs. “It’s still a challenge, particularly when I’m in new groups or situations and don’t feel fully comfortable or able to speak up for/as myself. But I’ve gotten a lot better at it over time, particularly with people or groups where I’m more settled.”

She encourages anyone of any cultural heritage to be gentle and patient with themselves.“Learning about and figuring out how to live as a disabled person in an ableist society is really tough, and it can definitely feel frustrating and overwhelming. So offering oneself grace is definitely a key component to navigating disability.”

More specifically for Asian folks, Hall shares: “Try to avoid comparing yourself and your experience with disability too much with non-Asian disabled people. Don’t judge or beat yourself up if your experience navigating your disability looks different.”

See also: Shedding light on the Asian adoptee experience

Where we are now: Reflections on the current disability landscape

Each of the changemakers featured in this article brings not only lived experience, but a frontline view of how the disability landscape has shifted and where it still falls short. Their perspectives paint a collective picture of an ecosystem in flux: one where progress and possibility coexist with systemic barriers and cultural silence.

Vanni reminds us that “we’ve barely moved the needle in terms of having authentic disability representation in media,” especially in light of recent industry contractions. While there’s greater awareness in some circles, she notes proposed policy rollbacks to Medicaid and SNAP disproportionately harm disabled and underserved communities, signaling how urgently community and cross-sector allyship are needed.

Khris sees momentum building: “It’s still messy, still evolving, but there’s more momentum than there’s ever been.” He reflects on how many professionals like him are navigating overstimulation, exhaustion, and the pressure to mask, and how the system isn’t designed with neurodivergent needs in mind. Still, he believes “there’s a hunger for honest leadership and culturally rooted advocacy.”

Saran acknowledges visible progress, with more disabled youth stepping into rooms once closed to them. “But it’s not enough,” she says.“We need more disabled youth, especially from immigrant, BIPOC, and underserved communities, to be included in these spaces.”For her, it’s not about asking whether they belong it’s about making space.

Marisa believes that while the ADA was a major step forward, “there is a significant lack of BIPOC disability representation, especially among Asian Americans.” She emphasizes the need for more disabled leaders and visible role models within Asian communities, noting that shame and comparison still silence many.

Tiffany has witnessed more visibility and pride in recent years, thanks in part to social media and grassroots organizing.But she’s clear: “Ableism is still deeply embedded in our systems,” especially where it intersects with race, class, and gender.That’s why she wrote The Anti-Ableist Manifesto to demand deeper, intersectional change.

Jennifer offers a student advocate’s view of structural shifts. She highlights how UCLA and other universities have made strides, launching disability studies majors, cultural centers, and advocacy groups. But she also shares hard truths like being denied academic accommodations by a non-disabled professor. “There has been real change,” she says, “but it’s still up to us to keep pushing.”

Jenny sees the evolution of disability advocacy as part of a larger arc: “I think the disability landscape has been through so many ups and downs,” she says. While she credits decades of advocacy for legislative wins like IEPs and 504 plans, she emphasizes the need for broader representation in leadership. “It’s time (and long overdue) for us to have better lived experience representation of all kinds of race/ethnicity and cultures in legislative branches.”

Hari knows firsthand how exclusion operates in education and research. “There are but a handful of autistics with communication challenges like mine in higher education,” he explains. His own success required creating a path where none existed with mentorship, flexibility, and institutions that said yes.“A key factor for my success was that no one at UC Berkeley ever said ‘NO.’”

Maddy observes slow but meaningful changes in the media industry. After consulting on Disney’s Wish, she believes the tide is turning. “I never dreamed I would ever see a character like me, much less work on it.” But she’s also quick to add: “There is no representation without accessibility.” She’s now focused on organizing for disabled artists in her hometown of Dallas.

Olivia sees greater public respect and awareness than in previous generations, but also more misinformation and government rollbacks.“There’s still a lot more progress to be made, especially around non-apparent disabilities,” they note. But they remain hopeful that disability will become increasingly integrated with cultural heritage and community understanding.

See also: 11 films and videos to watch centering autistic Pan-Asian experiences for Autism Acceptance Month

A vision for the future of AAPI disability advocacy

From culture to care, every changemaker we spoke to shared powerful visions for what the future can hold when AAPI communities embrace disability fully:

Vanni Le: “I would love a world in which everyone can just exist as themselves.” Le wants people to realize that EVERYONE has access needs and accommodations; the only difference is that certain communities have simply just always been accommodated.

Khris Baizen: “I envision a future where neurodivergent AAPI professionals are believed without needing to prove their pain. Where leaders recognize that real leadership is about who creates space for others to speak safely.”

Saran Tugsjargal: “I envision a future where AAPI disabled representation isn’t rare it’s everywhere, where their stories are not silenced out of shame but celebrated out loud.”

Marisa Hamamoto: “I want to see more representation of disabled Asian Americans.” Hamamoto hopes to dismantle the shame and comparison culture often present in Asian families: “There’s this culture of comparing your kids to other kids […] and that’s gotta go. Each child and person is unique. Their success is going to look different and that’s it.”

Tiffany Yu: “I envision a future where disability is seen as part of what makes the Asian American experience richer, where it’s included in our family conversations, cultural narratives, and leadership. ” Yu hope future generations feel proud of who they are and know they don’t have to be ‘fixed’ to belong.

Jennifer Miyaki: “I envision a future of disability that is more intersectional, accessible, and representative of diverse AAPI experiences.” Miyaki emphasizes the need to uplift marginalized stories within the community, including BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, immigrant, low-income, and AFAB individuals.

Jenny Mai Phan: “I envision a grassroots movement to fight hard, maybe even harder than we’ve ever fought before, for a moral society.” Phan imagines a future where our treatment of disabled people reflects our societal values. “It’s not just about inclusion, it’s about culture, care, and humanity.”

Hari Srinivasan: “I envision a future where disability is no longer something to hide in the Asian community, but something to understand, support, and integrate into every space—from classrooms to boardrooms.”

Maddy Ullman: “I want to see more dynamic, disabled, complex Asian characters on screen. I envision a future full of community, representation, and accessibility. I don’t want to be the only one in the room with a wheelchair.”

Olivia Hall: “I envision the future of disability for AAPI folks as continuing to improve in understanding and awareness about disability and for it to become increasingly integrated with cultural heritage and backgrounds.”

A heartfelt thank you to the ten changemakers: Vanni Le, Khris Baizen, Tiffany Yu, Jenny Mai Phan, Marisa Hamamoto, Jennifer Miyaki, Saran Tugsjargal, Maddy Ullman, Olivia Hall, and Hari Srinivasan, who all shared their stories with us so generously. Your honesty and brilliance are helping reimagine what disability, pride, and community can look like now and for the next generation.

Disability Pride Month isn’t just about celebration, it’s about reclamation. These ten disabled changemakers aren’t just taking space, they’re building it.

Not just for themselves, but for every disabled Pan-Asian child, parent, elder, or professional who’s ever been made to feel like too much or not enough.

They’re proof that being disabled and Asian isn’t a contradiction. It’s a story worth telling. And if you’ve been searching for your place in it, welcome. You belong here.

See also: Breaking free from the model minority myth as a neurodivergent Vietnamese American