April 30th holds a deep, complicated place in Vietnamese history. Known as Black April or Tháng Tư Đen among the diaspora, it marks the Fall of Saigon in 1975, the end of the Vietnam War, and the beginning of mass displacement for millions of Vietnamese people.

In Vietnam, the same date is celebrated as Ngày Thống Nhất (Reunification Day), but for many overseas Vietnamese who had emigrated from the homeland, it is a day of remembrance, grief, and reflection on the losses, traumas, and survival that shaped their lives across continents.

April 30, 2025, specifically marks the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam American War.

A new wave of people and a new way of life

Now, 50 years later, Vietnamese-Chinese American filmmaker Elizabeth Ai brings a powerful new perspective to this legacy through her documentary New Wave. As a career producer, this is Ai’s directorial debut, where she challenges herself and her subjects to go beyond the surface and deep into layers of not just trauma, but also joy.

‘New Wave’ is a musical genre from the late 70s and early 80s – a distinct mix of pop, synth, punk, disco, and reggae. The sounds of new wave are synonymous with playful, bold colors and unconventional mixtures of clothing materials and textures, bold jewelry and hairstyles, embracing both androgyny and flamboyance.

Being a ‘New Waver’ meant that you would assert yourself as both an individual, but also as part of a collective. It also meant being in community with other Vietnamese refugees striving to move beyond the trauma by reinventing oneself and creating a new sense of belonging in America.

At its heart, Ai’s New Wave documentary feature film captures the spirit of the 1980s Vietnamese New Wave music scene in Orange County, California, a subculture where refugee youth, carrying invisible scars from war and displacement, found freedom and self-expression through mile-high hair, synthesized beats, and rebellious fashion.

Finding joy after trauma: The story behind the New Wave documentary

The film includes a range of interviews with New Wavers and archival photos and footage from the film’s subjects as well as Ai herself.

For teens whose parents carried the weight of survival, New Wave became a language of identity, defiance, and belonging.

“Initially, this project was meant to be a straightforward music documentary,” shares Ai. “But as I spoke to my aunts, uncles, and community, it evolved into something much deeper, a personal story about trauma, memory, and the healing power of reclaiming joy.”

The film’s narrative is driven through Ai’s own childhood memories: riding in the backseat of her uncle’s car, windows down, new wave music blasting from the speakers, with the stories of the first generation of New Wavers.

“It seemed as though the music carried our sorrows away, offering brief reprieves from a life framed by a tumultuous home, undiagnosed PTSD, and numerous hardships,” shares Ai.

Bridging and healing generations through music and representation

The rise of the New Wave scene also paved the way for cultural icons like Lynda Trang Đài, often dubbed the “Vietnamese Madonna,” who dared to dream beyond the strict confines of survivalism.

Performing at nightclubs while telling her parents she was at church and bible study, Lynda Trang Đài introduced a new kind of representation for Vietnamese American youth hungry to see themselves reflected, but not without facing ageism and sexism along the way.

“I used to lie to my parents, telling them I was going to church, but really, I was putting makeup on in the car and going to the nightclubs to sing on stage,” Đài recalls.

Her performances connected generational divides, giving the older generation something to hold onto (nostalgia of their homeland, cultural pride) while inspiring the younger generation to claim space through music and storytelling.

“New Wave isn’t just a story about music. It’s a story about survival, joy, resilience, and about healing the silences between generations,” said Elizabeth Ai

Growing up Vietnamese American in the 90s

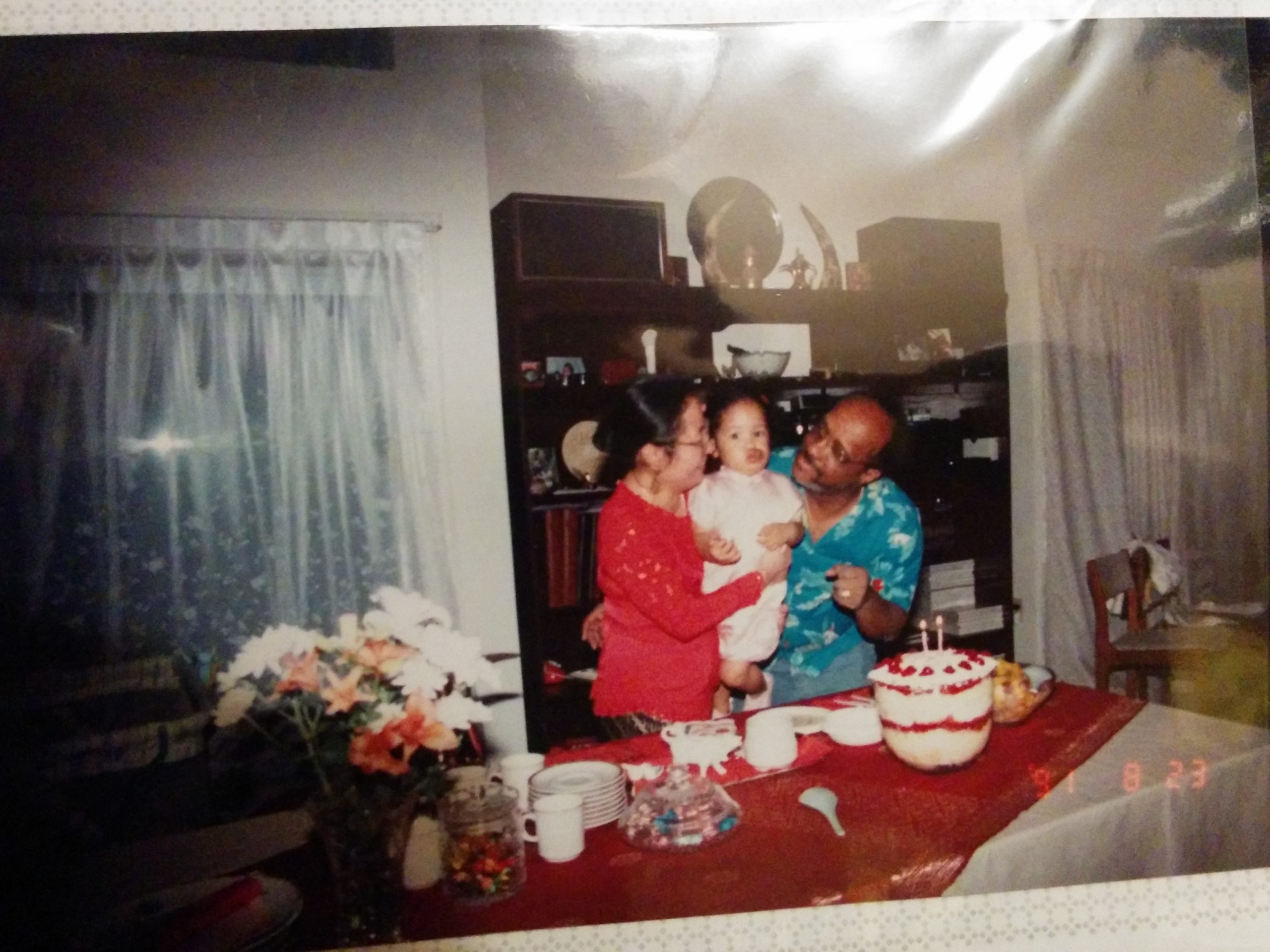

Watching New Wave felt like stepping into the echoes of my own childhood. As a Vietnamese American growing up in the 90s, I was no stranger to the complexities between family challenges and generational differences.

My family, like many others, carried unspoken grief, trauma, and high expectations. They, too, were hardly around. Work and financial stability were rooted in survivalism and necessity. Emotional conversations were rare; survival took priority. Pursuing creativity often felt discouraged in favor of practicality and stability.

Image adapted from: Thuy Nga

And yet, there were these moments of connection, fleeting but powerful. Sitting with my family and watching Paris by Night on rented VHS tapes became a sacred ritual. It was more than entertainment; it was a bridge between generations, between Vietnam and America, between grief and cultural celebration. Through music and performance, we connected with a homeland I had never seen but felt in my bones.

Like those in New Wave, I, too, craved creative self-expression while navigating the immense weight of intergenerational expectations while trying to fit in. I found refuge in storytelling, in singing, in dancing, in sharing meals and laughter with my community.

This is why New Wave resonates so deeply with me. It is not just a story of a subculture, it’s a story of healing, of visibility, and of reclaiming joy across generations.

Starting the dialogue: Fifty Years Later

The release of New Wave is particularly poignant as it coincides with the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War.

As director Elizabeth Ai notes, this milestone offers an urgent opportunity for intergenerational dialogue around mental health, trauma, cultural identity, and reconciliation.

“I hope this film inspires audiences to initiate intergenerational dialogue within their own families and communities,” she shares. “It’s never too late to start these conversations and to explore the complexities of our relationships and histories.”

In capturing both the pain and beauty of the Vietnamese American experience, New Wave invites viewers to not only witness history, but to heal through it, to celebrate the joyful defiance of a generation that dared to dance, even under the weight of their parents’ sacrifices.

More than a film: A movement of storytelling and healing

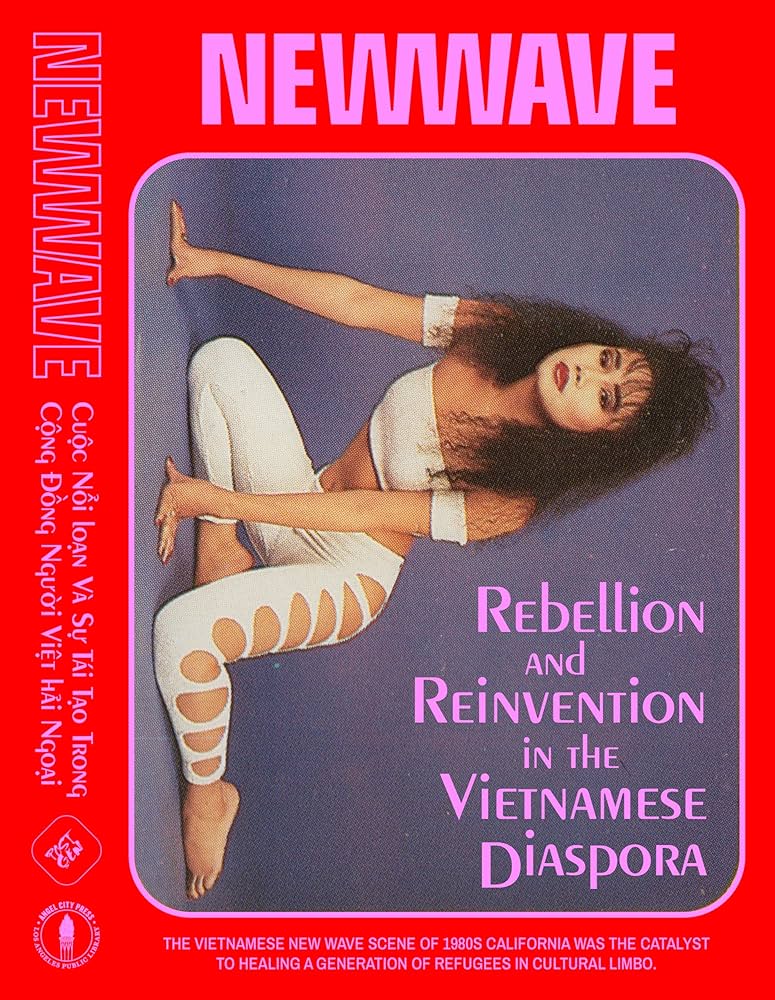

Alongside the film, Elizabeth Ai also released her companion book, “New Wave: Rebellion and Reinvention in the Vietnamese Diaspora” (2024), which expands on the film’s stories through essays, historical context, and personal reflections. It’s available now wherever books are sold.

Together, the film and book are a call to honor the past, celebrate resilience, and keep dreaming boldly into the future.

Learn more about the film and screenings at newwavedocumentary.com or request a screening in your hometown.